Colorado and Washington state recently decriminalized marijuana, once again giving voice to the national divide over our contentious drug enforcement policies. While various groups continue to debate the legal, medical, social and economic factors, one industry has managed to steadily flourish: private prisons.

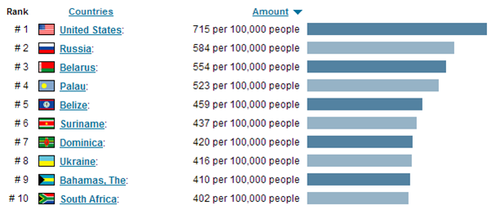

The United States currently has the highest incarceration rate of any nation on Earth. We put more of our citizens in jail than any of the religious theocracies, despotic tyrannies or war ravaged military states we decry in our media. No society in history has imprisoned more of its citizens. It seems there is a criminal epidemic in the land of the free…or perhaps we’re not as diligent in safeguarding our liberty as we’d like to believe.

By now, most have heard the statistic: “America comprises 5% of the world population, but has 25% of the world’s prisoners.” But why is that the case? Which group of ‘offenders’ is most responsible for this soaring increase? The commonly credited cause tends to be the ongoing “war on drugs”. While other crimes may only have one lawbreaker, the drug trade provides targets for arrest on both the consumer and provider side. Moreover, crimes such as theft, assault and even murder can usually be tied back to the drugs. It’s interesting to note, however, that violent crime rates in America have significantly dropped over the years. Moreover, most people in the American prison system are serving terms for non-violent crimes. Before we can fully understand the nature of our current penal system, we must first take a deviation into the history of our drug enforcement policy.

The truth is, the priorities and implementation of the war on drugs have shifted with each passing decade, leaving a complex state of conflicting interests in its wake. Nixon first introduced the program as a social welfare campaign, where most of the funds were primarily dedicated to rehabilitation and medical services. During the 1980s competing cartels turned Miami into a war zone, and policy focus was shifted to law enforcement accordingly. The nation was suffering a recession, but the Floridian party-capital was thriving under the influx of cash dealers were bringing in. They had a hand in almost every aspect of the city’s economy, sudden urbanization, land development and skyscraper construction. But this prosperity came at the cost of constant graphic violence that the city was ill equipped to police (leaving a murder count in Miami that was almost higher than the rest of the nation combined.) It was only after Reagan utilized the military to attack the cartels in their South American bases that crime in America returned to normal. But why was the program allowed to continue in this new direction after the threat was dealt with?

Well for one thing, those agencies which had flourished under increased funding were reluctant to relinquish their newfound power. Just like Homeland Security must justify its bloated budget as it strives to “prevent another 911”, the Drug Enforcement Agency saw a potentially continuous source of profit in globally targeting the trade. Recent Rico laws have allowed local police and federal agents to keep the money they seize from drug busts, incentivizing them with a financial motivation over a moral one. Police officers working on murders or white collar fraud can take months to build a case, while their drug focused colleagues rack in daily busts and gain promotional advantage. This creates a culture of prioritizing drug related targets over any other form of crime. Furthermore, pharmaceutical companies and alcohol lobbies have been very eager to villainize the “drug menace” and keep another competitor out of their market. Leaving the final link in the chain to grow unchecked: the prison industrial complex.

Many predicted that the war on drugs would fail, most notably Milton Friedman (President Nixon’s former election advisor, free market economist and Nobel Laureate.) Friedman was an avid scholar of the prohibition era of the 20s and 30s, and wrote a letter to Nixon at the onset of the war on drugs. Herein he described a likely pattern of events that would emerge, mimicking the chaos of the failed prohibition policies.

Milton explained that during Al Capone’s reign over Chicago, American’s desire to drink was not extinguished by the new laws. Instead, they were forced to find illegitimate sellers and suffer the harms of products created under reduced quality controls. Buyers were motivated to stray away from soft drinks like wine and beer, and explore quicker extremes in hard liquor (which profited the bootleggers as well.) Those criminals providing consumers with alcohol cared little for their safety, well being or budgets. A now unreasonably expensive habit caused increases in crime to pay for it.

But Friedman saw new dangers in the criminalization of drugs as well. He predicted that an impressionable youth would find the “forbidden fruit” of drugs more seductive. He knew that competing dealers would be incentivized to brand themselves by creating the most potent products on the market. He knew that if drugs were no longer classified under the canopy of a health issue, users would feel like criminals and be far more reluctant to seek help. Friedman explained that the duality of consumption and alienation from the law, would cause citizens to have decreased respect for the other laws of society. The overnight portion of society that were suddenly labeled criminals, would require police forces to move away from other crimes to deal with them. Furthermore, criminals with large profits would more effectively bribe police and judges, reducing the legitimacy of the legal system.

It is a sad state of affairs, that we so wholly embody a forty year old prediction…

There is no doubt that drugs can harm the individual, families and even communities. But it is important to distinguish the harm caused by the substance, and the harm caused by the prohibition. The misguided laws created for this “cure” only add to the misery. Those very same dangers we were warned against: unknown substances, from unknown sources, with unknown effects are a direct result of laws not the substances themselves. Decriminalization can lead to regulation, quality control, researched medical advice and treatment. Instead, the chaos created by these laws is used as justification to defend them. It’s a vicious self-repeating cycle that has gone on for far too long. So why hasn’t it stopped?

That brings us back to one of the most deplorable industries profiting from this public misery: Private Prisons.

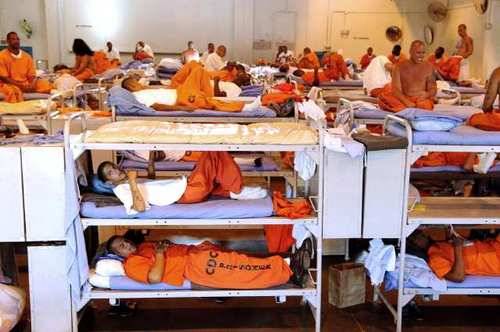

Before we examine the mechanics and distinctions of private prisons, let us come to grips with the relevant statistics. In 2008 approximately one in every 31 adults (7.3 million) in the United States was behind bars, or being monitored (probation and parole). The breakdown for adults under correctional control was as follows:

- 1 out of 18 men

- 1 in 89 women

- 1 in 11 African-Americans (9.2%)

- 1 in 27 Latinos (3.7%)

- 1 in 45 Caucasians (2.2%)

- 1 in 89 women

- 1 in 11 African-Americans (9.2%)

- 1 in 27 Latinos (3.7%)

- 1 in 45 Caucasians (2.2%)

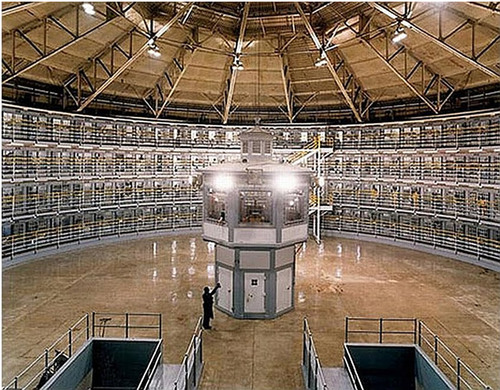

Private Prisons, and the various businesses that supply them, have been advocating for ever increasing control over the national prison population, under the guise of offering a more “efficient” alternative to state run facilities. Construction firms, surveillance companies, guard unions and several other businesses have aligned themselves with this ever growing industry. On top of being paid by the states to house each criminal, private prisons are also permitted to transform their prisoners into a work force. Aside from construction, field work and other physical labor, prisoners in America produce all military helmets, ammunition belts, bullet proof vests and ID tags. They account for 98% of the total market for equipment assembly services. They make 36% of home appliances, 21% of office furniture and 30% of all microphones, headphones and speakers.

For the corporate owners of these private prisons, this is like winning the lottery. They own a labor force which the government pays them to house, making money on both ends. America has strict laws that prohibit the importation of products made by slave labor abroad. Meanwhile, we’ve essentially reinvented slave labor at home. Prisoners can of course refuse to work, but they face solitary confinement as punishment.

Prison Industry-funded studies have concluded that states save money by using private prisons. However, state-funded studies found that private prisons keep only low-cost inmates, sending the rest back to state-run institutions. Evidence has shown that private prisons are neither discernibly more cost-effective, nor more efficient. Our antiquated and ineffective war on drugs, has become a war on the poor. It feeds those who cannot plea or pay their way out of harmless drug possession charges into a forced labor machine.

“In the past two decades, the money that states spend on prisons has risen at six times the rate of spending on higher education. In 2011, California spent $9.6 billion on prisons, versus $5.7 billion on higher education….. The state spends $8,667 per student per year. It spends about $50,000 per inmate per year. Why is this happening? Prisons are a big business. Most are privately run. They have powerful lobbyists and they have bought most state politicians. Meanwhile, we are bankrupting out states and creating a vast underclass of prisoners who will never be equipped for productive lives.”

— Fareed Zakaria, CNN, March 30, 2012

The success of these prisons is a reflection of the failures in our campaign against drugs. The Amsterdam model is often utilized as an example of functioning drug policy. A less known success case is Portugal, where over ten years ago all known drugs were decriminalized. They have since reported dramatic drops in their crime rates and drug related health problems. The World Health Organization and United Nations have both advocated Portugal’s example. South American countries have begun to follow suite, most notably in Guatemala where President Molina has called for legalization.

What may have begun as a campaign against the specters of addiction, crime and destruction, has since grown into a creature that feeds itself on the vulnerabilities of the impoverished. The war on drugs is a terrible injustice and should have ended 20 years ago. Our methods have been proven utterly ineffective. Industries have grown on the backs of citizens who have been torn from their families and communities. Despite all this, the demand for drugs has only increased. There are a surplus of solutions available to explore, the only certainty is that our current policy is no longer tolerable.

No comments:

Post a Comment